|

James P. Othmer

James P. Othmer

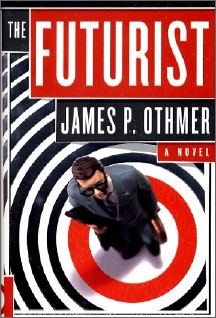

The Futurist

Reviewed by: Rick Kleffel © 2006

Doubleday / Random House

US First Edition Hardcover

ISBN 0-385-51722-X

Publication Date: 06-06-2006

260 Pages; $23.95

Date Reviewed: 06-25-06

Index:

General Fiction

The popularity of characters described by the phrase "love to hate" should tell us something about ourselves, and it's not flattering. Unless of course you're heartened by the knowledge of the conflicts within us, the assurance that we're as complicated within our own beings as the world around us. But the act of reading is nothing if not complicated. It demands mental gymnastics that are clearly not well understood, even by those who love reading. Yet it is not required that one understand an act to enjoy it. In fact, sometimes too much understanding gets in the way of enjoyment.

Yates, the protagonist of James P. Othmer's novel 'The Futurist', understands nothing while he appears to know everything, or at least enough to espouse what seem to be informed opinions of what’s coming down the pike. As a futurist, he's all presentation and no content. He's a bad futurist, with a staff of one whom he generally ignores, in favor of making up what the clients want to hear. In fact, as a character, he starts out, at least, as all presentation and no content. Othmer's novel charts an eclectic course. Written in wall-to-wall sound bytes, it's vitriolic satire one moment and searching, self-revelation the next. Just when you think you have a unique thriller on your hands, it goes surfing. And about the time you're engrossed in tour-guide zen wisdom, it blithely picks your pockets of any grains of sympathy and throws them to the winds. Like all your most intense relationships, 'The Futurist' is filled with pandering promise and tear-inducing disappointments.

Yates' journey to the end of the novel — he's not engaged in a search for self-enlightenment — begins shortly before the FutureWorld Conference in Johannesburg. He gets a handwritten note from his girlfriend that tells him he's being dumped for a sixth grade history teacher. As his world seems to be crumbling anyway, he decides to give it a helping hand. Lubricated by tiny bottles of hotel liquor, he gives an anti-keystone speech at the Conference, deeming himself the leader of the "Coalition of the Clueless". Hungover and despondent, he waits for his working life to end. Instead, he's hailed as an honest voice and hired by a shady quasi-governmental organization that offers him a blank check to jettison his infant conscience and travel the world and find out, wait for it, "why they hate us."

Othmer, who spent more than twenty years in advertising, knows better than most why they hate us. Yates' journey, internal and external, no strike that — Yates has no internals. Yates is all surface, and Othmer's prose does an outstanding job at conveying the here-and-now. The novel is written in the present tense. (If you hate novels written in the present tense, you’d better learn to love to hate novels in the present tense, otherwise, you'll end up hating 'The Futurist'.) It's peppered with "He once..." moments, pithy bits of banal horror such as, "He once fired a man on Take-Your-Daughter-To-Work Day." If you want to call 'The Futurist' a satire, and expect laughs, then you’re good. 'The Futurist' does at least incorporate satire, and it is frequently very funny. But 'The Futurist' is quite a bit more than satire. Othmer's prose takes the reader on an effortlessly imagined global tour, from Fiji to Iraq-stand-in, from heaven to hell. Not a lot of difference, it seems. Well, in hell you’re a lot more likely to get blown up.

Some readers may have a bit of a hard time with old Yates. That phrase, "love to hate" often loses the "love to." But Othmer's engagingly glib style manages to keep our hate on the surface. Fortunately, Yates is not our only company in Othmer's SurfaceWorld tour. He provides a series of more engaging moral counterweights to Yates, from Marjorie, the white South African prostitute with whom Yates does not (at first, at least) have sex to Blevins, Yates' long suffering assistant. If the mark of a good novel is that you want to see more of characters, then this is a good novel. You'll likely wish that there were more Blevins here, but Othmer's smart enough to leave you wanting more rather than making you wish you had less. Twenty years in advertising will do that.

The plot and tone of 'The Futurist' are both really quite clever. Othmer is entertainingly loose. He doesn't adhere to any convention whatsoever, and it keeps the novel feeling fresh at every point in the proceedings. There are elements of a gripping thriller where the thrills transpire off-screen, a novel of self-discovery about a man who has no self to discover, a funny send-up of the sub-culture of talking heads and a dysfunctional family story about a family that works quite well, thankyouverymuch, though dad's dead and mom likes to watch CNN while eating from a TV tray. To Othmer's credit, he manages to step from one fresh hell to the next without disturbing the reader's sensibilities. As you read 'The Futurist' you will feel just as glib as the title character.

For a novel that is all surface, 'The Futurist' manages a few surprising depths. These are diving bell moments of literature, glimpses of the real world through a tiny, thick glass. But just as it takes only a simple flip of the emotions to turn hate into love, or vice-versa, 'The Futurist' occasionally manages to invert and become quite intense, quite memorable. It's far too funny and enjoyable to be literature, but then, sometimes we love to hate literature, so perhaps 'The Futurist' will have to do.

|

|