|

Gregory Frost

Gregory Frost

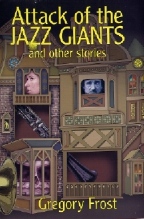

Attack of the Jazz Giant

Reviewed by: Terry Weyna © 2005

Golden Gryphon Press

US Hardcover First

ISBN 1-930846-34-7

Publication Date: June 2005

344 pages; $25.95

Date Reviewed: July 5, 2005

Index:

Science-Fiction

Horror

Fantasy

General Fiction

Reading Gregory Frost's 'Attack of the Jazz Giants' is like wandering through the best exhibit of surreal art you've ever seen. Look — there's a Magritte! And over there — those bizarre Max Ernsts and de Chiricos, next to Dali's melting watches! Of course, it doesn't hurt at all that Jason Van Hollander's highly surreal art, spooky and beautiful, is found throughout the book, in incredible pen and ink sketches. (The exquisite wrap-around cover also serves as the opening page to Frost's website).

It's astonishing to find that Frost has been writing exquisite short stories for more than 20 years now; he has certainly kept a fairly low profile. And that's a shame, because he is extraordinarily gifted in the short form, one to be discussed along with John Kessel and James Patrick Kelly. Frost's stories are ignited by a dark, rich anger, a fury at injustice at the turn of the 20th century, and sheer hatred of an individual's inability to force an immediate, major change in the circumstances of those who live lives of quiet desperation.

The anger is most apparent in what is probably Frost's best-known story, "The Madonna of the Maquiladora." This exquisite story, for which Van Hollander provides two glorious illustrations, takes place in Juarez, Mexico, a city despoiled by factories that operate without restrictions, free to pay employees a mere $25 per week and to deposit harmful industrial waste wherever they damn well please. Why do the employees — the esclavos de la maquiladoras, the factory slaves — stand for this? Why do they live in such squalor? Perhaps it's because the Madonna appears to Gabriel Perea, one of the workers, and tells him that he and the other esclavos will see their reward in heaven. Is it truly the Madonna? Or is it a trick by the maquiladoras? This bitter story shows religion and capitalist greed in a gruesome partnership, exercising control over a seemingly docile group who are quickly working themselves to death for a promised life beyond the grave. This is not a comfortable read, for it is too close to the truth of the Church in South and Central America. It is not a story that you will ever forget.

"The Bus" is equally angry, if directed toward a different sort of city in a different part of the world. It is a story about another species of throw-away humans, the kind you and I probably pass each day on the street, the kind that we're told by our cities not to help out on the grounds that that only hurts them when what they really mean is that these folks hurt the tourist trade. Life's a big party, but not for these folks, and yes, I am getting angry just remembering these stories. Frost doesn't make things easy for his readers.

"Collecting Dust" is another tale of the anguish of modern life, but it is set in middle America rather than among those who live in the depths of poverty. It is such a perfect picture of how work swallows life in these days of stagnant incomes and rising material expectations that it will make any wage slave take a close look at how she lives her life. This story is sad, quiet, and ravages the soul.

Magritte would have loved the title story of this collection, "Attack of the Jazz Giants," in which exceptionally large musical instruments begin appearing mysteriously in the night on a plantation which is still kept afloat by slaves more than a century after the end of the Civil War. And who better to wreak vengeance on the Grand Cyclops of the Klan and his family than those masters of the only truly American musical form? The story is simultaneously beautiful and ugly; it made me think of Magritte's "The Rape," which I could only view for a few moments before it made me turn away in simultaneous appreciation and revulsion.

"Touring Jesusworld" is another look at the perversions of religion in modern life, a story that makes perfect sense in a world where the Supreme Court has just ruled that a display of the Ten Commandments passed constitutional muster if it's placed in the public square as part of the promotion of a hokey movie starring Charlton Heston. This little story hits the high notes of corporate religion with a ringing tone.

"Lizaveta" and "In the Sunken Museum" partake of a different sort of darkness, a more Lovecraftian darkness in the first, and one in the style of Poe and staring that master of horror himself. Both cast spells of gathering horror as the tales are told, and are best read with the lights on all over the house. "From Hell Again" is Frost's Jack the Ripper story — so many SF writers have written of this mysterious character, from Harlan Ellison to Alan Moore to Jack Dann, and Frost is comfortable in their company. Van Hollander's illustration for this story is his most reminiscent of Max Ernst, a lovely drawing of the utmost weirdness.

Frost also gives us several stories on a lighter note, but still in the dark and creepy range. One of my favorites is "The Girlfriends of Dorian Gray." This horror story combines two of my personal delights, Greek myth and food. How to keep the pounds off? Oh, there's a way, all right. "How Meersh the Bedeviler Lost His Toes" begins, "You know this story already," and indeed you do, in a sense, provided you have read deeply in the myths and fairy tales of many cultures and don't mind rereading them set askew so oddly that you're not quite sure where you are.

There's a touch of light humor, too, in "The Road to Recovery," a Bob Hope/Bing Crosby pastiche that is original to this collection. This story perfectly mimes the wackiness of the old "Road" movies, where everything goes wrong and then comes right and they get the girl, besides — and they do it in deep space. Even if you're not a fan of Hope and Crosby, you'll enjoy this romp.

Every now and then —rarely, actually — Frost misses altogether. "A Day in the Life of Justin Argento Morrel" is an attempt at metafiction utilizing all of the stock SF characters that have arisen, mostly from television, over the years. Frost can't quite pull off the satire. "Divertimento" has a frightening idea at its core — a "time bomb" that ages the people caught in its blast, while bringing historical moments into the present like pieces of film, playing over and over again. But it is too big an idea for the mere fillip of a story we get here. "Some Things Are Better Left" is a vampire story of sorts that is, well, better left. But these stories are by far the exceptions, and make me no less eager to turn next to Frost's recent novel, 'Fitcher's Brides'.

Perhaps the most amazing things about 'Attack of the Jazz Giants's is how very compelling it is. Most single-author collections almost demand to be read in the same manner that one eats a pound of fudge — slowly, a bit at a time, over a number of days. Even the very best authors have recurring themes that become uncomfortably noticeable in a collection, and little turns of phrase or samenesses of description start to have a prominence that one would not otherwise notice. But that's not the case with Frost's work. Every story differs radically from every other story. There are no similarities save the excellence of the writing. One can turn from one story to the next and be in a whole different world, an experience much more common to reading an anthology instead of a collection. This type of variety is extremely unusual, and extremely fascinating.

Golden Gryphon continues to provide us with the best collections available in the marketplace today. While the rest of the publishing world is, for the most part, avoiding short story anthologies and collections, Golden Gryphon is crafting books with care, giving us wonderful books that are beautifully made, beautiful to look at, and containing the very best in contemporary science fiction and fantasy. Long may they prosper.

|

|