|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

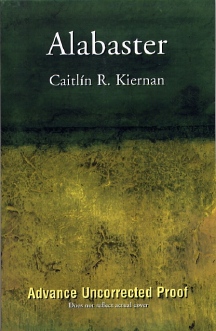

03-24-06: Caitlin Kiernan's Dancy Flammarion is 'Alabaster' |

||||||

Sub

Press Collects 'Em All

The Dancy Flammarion stories are what you might have hoped for had Flannery O'Conner read way too much H. P. Lovecraft in her formative years. Kiernan, of course, is a fierce individualist. She does both what she can and what she wants to do, and her influences here are also to be found in the name that she chooses for her character. Dancy, well, that's just odd, but the Flammarion part -- there's a science fiction writer attached to that name. Cue French astronomer Camille Flammarion, whose life spanned two centuries. He was born in 1842 and died in 1925. In the intervening years, he wrote more than 70 books, of non-fiction and science fiction. He was one of the first writers and thinkers to conceive of truly alien species, that is, critters that weren't just "space humans", but you know, sentient space plants and sentient space monsters.

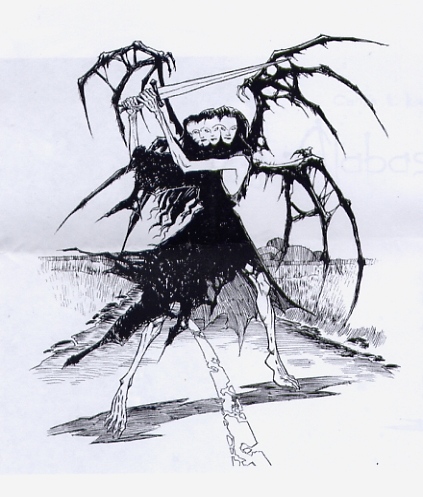

But Flammarion wasn't just a monster-hound or a space case. He was devoutly religious, and combined his religion with his science fiction, making him to a certain extent, a precursor of Elron Who Bard. He believed that humans were "citizens of the sky" and wrote 'La pluralité es mondes habité' (The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds). This whole pluralism deal is pretty interesting, as it was the first organized belief that life and indeed intelligent life might be found on more than one world. Not only was he a proto-$cientologist, he helped to create a sort of proto-SETI as well. Sure, that's stretching the point, but you should get my drift. He was a scientist, a science fiction writer and something of a visionary. And that brings us right back to earth and Caitlin R. Kiernan. Her character is certainly a visionary, and inclined to visions of alien critters, in fact, rather religious visions as far as that goes. Basing her first Dancy Flammarion story on a passage from 'Threshold' and the illustrations of Dame Darcy, she created 'In the Garden of Poisonous Flowers' for Sub Press. By the time that had been published, she'd finished a second story about a character she intended to punt. And so it goes for the actual writer; characters talk to you and damn if you don’t have to listen, and eventually write down what they tell you, no matter what they say or how unsellable it might at first seem. 'Alabaster collects five stories with an entertaining preface and afterword. The stories appeared in so many places -- including Gothic.net -- that you might as well give up in advance your hopes of finding them elsewhere, especially since some of the versions here are massaged and expanded. And you won’t find them elsewhere with the Naifal illos either. So just give it up, and hit up Sub Press for the latest Kiernan collection. It's not eye-wateringly expensive, nor is it eye-wateringly long. By the time you're able to read, however, the shadows will be growing longer. Within them will be deeper shadows. And emerging from those shadows, well...Dancy could tell you what to expect. |

|

03-23-06: Jonathan Kellerman and Lisa Gardner Are Both 'Gone' |

|||||||

The

Presence of Absence

It's pretty hard to miss. Two novels by prominent, mainstream mystery writers, both titled: 'Gone' What is it about our culture, our literature that gets under our skins, into our brains and most importantly -- into the machinery of the very same publisher to offer two books with the same title and theme? What is it that is missing in our lives that makes us want to experience the presence of absence? There are definitely Fortean forces at work here. First off, let's take a look at the books themselves. Lisa Gardner was the first out of the gate with 'Gone' (Bantam / Random House ; February 7, 2006; $25.00). In a sense, you couldn’t ask for a more perfectly designed mystery-suspense bookselling machine. You've got Pierce Quincy, a main character, who was once an FBI profiler. This FBI, it's a family thing -- his daughter, Kimberly is a rookie FBI agent. Think she'll make the big leagues? Little does she know she's already done so, as this is the fourth book in a series that began with 'The Third Victim.' Quincy's estranged wife with a troubled past? That's Rainie, and she goes missing, if you believe the cover, in the rain. So, series fiction–check, profiler–check, rookie–check, troubled past–check. Gardner whips together a check-your-brain-at-the-door page-turner, the kind of novel we'd call a beach book if it weren't raining both outside our houses and in the novel itself. I'm guessing that later this year, the mass-market paperback might indeed become a beach book. This is not literary science, it's TV science, but good TV science, well-written , suspenseful and gripping. Gardner's 'Gone' is a fine novel that holds your interest and merits turning off the TV. But rattling around in there is something very important; our fascination with those people who leave us and never, ever return. With this missing-person premise, Gardner has managed to tap deep into the American psyche. Hot on her heels is Jonathan Kellerman with 'Gone'(Ballantine / Random House ; April 2006; $26.95). This novel, the latest in Kellerman's every-popular Alex Delaware series, starts with the traditional kidnapped students. One must presume they had sex before being kidnapped; after that, the universe punished them in the usual fashion. But the missing person premise is only the beginning. Kellerman layers the disappeared person incident with the ever-popular criminal hoax; and then things get nasty. Rest assured that you've learned less here than you will if you make the mistake of reading the dust jacket, which doesn't ruin as much of the book as you might suspect. Kellerman takes his characters and the missing premise considerably further afield than Gardner, but in similarly slick page-turning style. Those who are addicted to his work will want to snap this one up, and are likely to turn it into another entry in the bestseller lists. Still, like Gardner, Kellerman is mining something a bit deeper than next week's beach book. It might be steeped in car chases, draped in murder and handily solved -- after a few murders are revealed -- by Alex Delaware. But Delaware is staring into something deeper than a patient's eyes. He's looking at the presence of absence.

Of course, we know there are any number of reasons to do so. Here in modern America, debt is a pretty compelling reason to vanish. Infidelity is another good reason to get out of Dodge. But it's a short step from debt to death, and perhaps, in the end, this is the reason that vanishings are so important, so interesting to readers. For all we know about death, it does reduce to the fact that a person has vanished, so far as we know. Sure, we can see the body buried, and visit the grave -- or the urn -- but these in-the-life vanishings are no more or less mysterious than death. And those left behind actually have a better, wider range of imaginative response to the vanished than they do to the dead. No matter what your beliefs as to what life after death may be, it's easier to envision the absent in Havana than in Heaven. The disappeared are more easily dispatched to an eternal reward than those who are buried before our eyes. The other attraction of the absent is its opposition to the increasingly cluttered present. We're surrounded by stuff, both physical and mental. There's more stuff for us every single damn day. There's more stuff to think about and there's more stuff to pick up, put away, to deal with. There are certainly more people to deal with. To read about those who disappear, to experience even vicariously the presence of absence is vital when you otherwise are allowed only to experience presence. Doing so when reading, especially when reading the sort of thriller that Gardner and Kellerman both excel at, offers a reader the chance to both make the world disappear and to disappear one's self -- into the pages of the novel. In fact, by reading we seek departure, to have the entirety of our lives vanish and be replaced with other lives, more troubled, more cluttered than ours. And when those within the pages we read simply go, our own absence is twice done. We open up the books, seeking the presence of absence, and ourselves, as we read, we are gone. |

|||||||

|

03-22-06: L. Timmel Duchamp, Always the 'Renegade' |

|||

Yesterday's

Dystopias Are Today's Headlines

As the novel begins, the characters have settled into one of those "you can get used to anything" dazes. This is one of the great downfalls of the human race, because, after long enough exposure, one must accept the current reality even if one wishes to change it. And the second you accept it, you've made a deal with the sort of devil who simply ups the ante and moves the goalposts, so that what you find yourself rebelling against, the order you find yourself hoping to restore is the order you were only years or months ago up in arms about. It's the subtle, insidious progress of dystopia. What I find interesting is that Duchamp's dystopia, conceived of over twenty years ago and revised for the current state of affairs over ten years ago, is becoming more, not less relevant. Her chaotic combination of feminist anarchy up against Executive civil war might very well have seemed dated in light of current events, but instead, it's starting to seem ever more prescient. Ever and again, we seem to find that yesterday's dystopias are today's headlines. But Duchamp doesn't need headlines to grab the reader. You do that with good writing and strong characters. Both are to be found in abundance in 'Renegade'. And I do mean abundance. This here is a 616 page pulse-pounding page-turner, based on Duchamp's research into the shenanigans and evil-doings of our own favorite set of spies, the CIA. What would happen to our bureaucrat-overseers, were they to be freed into a landscape overrun by near-civil war, greed and violence? No, this novel is not about current history or anything resembling it. You do, indeed, get hints of the truly alien. They're the seeds of change. Of course, the question you may find yourself asking is where the hell are the aliens now? I mean, get with it -- land already. We're getting pretty close to not caring if it's a cookbook. It's a pressure cooker down here anyway. One of the great advantages of publishing a finished-some-twenty-years-ago series is that it's, well, finished! I'm glad to see that Aqueduct Press is still going strong, with this release following hot on the heels of Andrea Hairston's 'Mindscape'. Readers won’t have to wait all that long to find out what the heck is going to happen when Kay Zeldin, rescuer of scientists and Elizabeth Weatherall, executive-in-charge of persecution. The next book in the Marq'ssan Cycle is due later this year, with the final two volumes to follow next year. That's a pace for change that I can live with, swift enough to draw notice, swift enough to ensure revolt. If only reality were so kind as to present it's changes in such a fashion. We'd know who to go after! Of course, one must remember that it took Duchamp some twenty years to bring this dystopia into being. And that should tell us something as well. Is this what we can expect some seventy years hence? We should know, then to look out for big-ol' speculative fiction series that come out sometime around the year 2050. Or, in 2048, keep our eyes peeled for 2084. And for those of you who are tired of reading the newspaper, of the endless parade of bad news, why just read yesterday's dystopian fiction. All you’re missing is the comics. |

|

03-21-06: Amanda Hemingway Draws 'The Sword of Straw' |

|||

The

Clockwork Trilogy

First, the odd, publisher-oriented obsessive book-collector-type news. Now, last year's debut was in a super-low-cost (but not cheaply made) trade hardcover. For $16.95, it seemed to me that they were giving away the store. Apparently, they were giving away the store. 'The Greenstone Grail' was recently re-released in trade paperback (at $12.95), and the sequel debuts in trade paperback at $12.95. I'm rather saddened the super-cheap hardcover strategy didn't work out. I really liked this idea, but then, it may have been just a loss-leading gimmick to get readers addicted to the series. Whatever the case, you’re not going to find a hardcover version to match up with the first installment. More's the pity. But -- whatever! At least Del Rey has not left us hanging. Yet. So, in 'The Sword of Straw', Nathan Ward is once again dreaming of parallel universes and other worlds. This time around, it’s the old sword-in-the-stone gig. The kingdom of which Nathan dreams is dying, rotting, headed to hell in a handbasket. To blame is that darned Evil Sword. Said sword is the residence of a rather nasty demon, the kind of crabby sumbitch what kills thems as has the noive to draw the sword. What do you bet? You think that Nathan, popping in in his PJ's is going to save the day? Shock me! OK, so surprises are at something of a premium here, but then, listen to the setup. Evil sword? Alternate universes? You've got to hand it to Hemingway for mining Michael Moorcock and not the usual J. R. R. Tolkien. Now, of course, there is a bit of standard-issue clue-collecting going on here. First he gets the Grail (if not the girl) and next he gets the sword -- well, one hopes. Next, presumably, he collects 'The Poisoned Crown,' the third novel in the series, due out in November in the UK from HarperCollins UK. It's pretty fascinating how fantasy series pop back and forth between different publishers in the UK and the US. Pratchett comes out from Victor Gollancz in the UK and he gets a HarperCollins release in the US; Hemingway gets a Voyager (HarperCollins UK imprint) release in the UK and ends up coming out from Del Rey, a Random House imprint, in the US. Oh the joys of obsessing over the minutia of books never end, do they? And since they never end, as I looked this up I found something I should have sussed a year ago. As it happens, Amanda Hemingway has written a series of very popular and highly-regarded novels under the name Jan Siegel; to wit, 'Prospero's Children', 'The Dragon Charmer' and 'The Witch Queen', published in the UK as 'Witch's Honour'. I remember when these were being published and I saw them at Logos Books, one after another; then, all together. I have to admit that I was intrigued at the time, and now it seems that it was with good reason. As it happens, The Sangreal Trilogy is being published in the UK, with November-the-year-before release dates. In fact, 'The Sword of Straw' is given the more ominous title 'Traitor's Sword' in the UK. So should your thirst be whetted to the point where you can wait no longer, you can pick up the final book in the series in a UK edition in November of this year. But the bottom line is that an author who mines Philip K. Dick, Robert A. Heinlein and Michael Moorcock is working in territory that is both fertile and intriguing. Whether she's Amanda Hemingway or Jan Siegel, she's an author worth watching, so long as you don’t mind adding to your already formidable reading queues! |

|

03-20-06: Cynthia Carr's 'Our Town'; A Conversation With Joshua Spanogle |

|||

It Could Have Happened Anywhere

But we're back with a serious-as-all-get-out Monday. Let's start with Cynthia Carr, who has for many years worked as an arts writer for The Village Voice. It's got to be a great gig, writing about the arts in New York for a respected and free-wheeling newspaper. But there was something in Carr's past. Marion, Indiana. We're all supposed to know the facts, but I'm going to run them by, just so we can all start on the same page. On August 6, 1930, three black teenagers were arrested, accused of killing a white man and raping a white woman. The next night, two of the men were dragged from the jail, beaten and hanged by an angry mob of white citizens. The moment was captured in an infamous photograph. The third and youngest, named James Cameron, was spared and brought back to the jail with rope burns around his neck. Cynthia Carr knew all about this, better than most. Marion was her father's hometown, and even as a young girl, she'd heard the story. But it wasn't until she was in her late teens that she learned her grandfather was a member of the Klu Klux Klan in Marion. She learned that she'd walked under the tree where the men had been hanged. She searched the infamous photo for her grandfather and was relieved not to see him there. Carr had long considered writing about the events in Marion. But she didn't do so until she learned that James Cameron was still alive. She arranged to meet him and 'Our Town' was essentially founded. But Carr spent ten years building this city, and the result is an astonishingly complex combination of true crime, social history and personal quest. This is the kind of writing that has the pull of a novel and the heft of history. Carr does not confine herself to her family history and the lynching itself. She goes back to the time when Marion was a stop on the Underground Railroad, and forward to 1998, when there was a public reconciliation ceremony on the courthouse lawn where the lynching took place. In terms of non-fiction, I'm reminded of the scope and feel of 'Big Trouble' by J. Anthony Lukas. 'Our Town' offers readers nothing less than gripping history, an incisive look at a divisive subject told with the toe-tapping plot details of a true-crime saga. This type of book is precisely why I write The Agony Column. Yes, I do love genre fiction, but I love lots of other stuff as well, and this type of reading is the sort of thing one reads before writing a decent piece of fiction. I have to admit that it took me only a second to think about the latest Craig Spector novel, 'Underground'. Yes, it’s true, I do read a lot of non-fiction with the idea that it provides grist for the fictional mill. But I also read it because when someone like Carr gets a grip on something powerful, something violent and dark like the events in Marion on August 6, 1930, that kind of reading is immersive in the exact same way that fantasy or science fiction is immersive. The writer creates a world for the reader. We may or may not live in that world. In the case of 'Our Town', one hopes the world we live in is very different. We've all come a long way from Marion, and yet, the journey seems short. No matter how you arrive in 'Our Town', it proves to be our world. No getting away. |

|||

Writing as Isolation

The conversation uncovered a lot of interesting background points that will, I suspect, sell lots of copies of Spanogle's first novel. He spent time as a Bioethicist and time reading Raymond Carver as well as Raymond Chandler. That's a very odd combination, but one that ensures his novel is a lot more complicated than one might surmise from the rather generic cover image. As usual, the interview is available as a MP3 download, a RealAudio download and as a Podcast. Do yourself a favor and buy the book before you listen. Spanogle is a fascinating guy with a great angle on his fiction. He hits all the techno-points of modern medical thrillers with a noir sensibility that is really appealing, especially in the midst of all that geekery. And he assures me that he is not is title character, which bodes well for his future patients. |