Words & Pictures

A Reader's Guide to Reading Graphic Novels

The Agony Column for December 31, 2004

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

A Reader's Guide to Reading Graphic Novels

The Agony Column for December 31, 2004

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

Click here to see a gallery of huge images from the works reviewed!

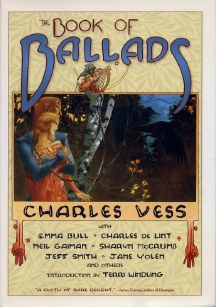

That was almost ten years ago, and in the intervening years, plenty of graphic novels have popped up that were clearly worthy of my attention. But that didn’t get them read, even though I bought a Neil Gaiman hardcover from DC comics earlier this year with the express purpose of reading it. For the time being it appears to have disappeared into the bowels of my library, though there's some slight possibility that my oldest son took it to art school. OK, but the upshot of this is: not read. So what finally forced my hand? Well, as you might expect it was confluence of incoming books. From the second I saw the Charles Vess collection 'The Book of Ballads', I knew that I wanted to read it. This hardcover "graphic novel" from Tor was beautifully produced and extremely tasteful. As someone who has campaigned for more illustrated books -- especially if they're illustrated by J. K. Potter -- you'd think I'd really like graphic novels and welcome more rather than less illustrations. But the thing I liked about the Tor title was that it was entirely in black and white. It really looked like a book. And tasteful? You don't get more tasteful than Charles Vess, whose work I'd previously enjoyed when I came across an illustrated edition of 'Stardust' by Neil Gaiman. But that was an illustrated book, not a graphic novel.

After all, I'd done so for ten years. Now, don't take my disinterest for a lack of respect. There are reasons for my willingness to avoid graphic novels. For one thing, I like typeset type. Hand lettering is hard for me to read. And there are certainly more than enough typeset novels to keep me busy. As I fell further and further behind in the graphic novel genre, I grew more and more despondent as to my ability to ever catch up. Furthermore, I wondered which graphic novels would stand the test of time. Books and authors certainly had -- not all books, and certainly not all authors, but the categories had. Really, all I had back then was 'Watchmen' to cling to, which was clearly the work of a superior writing talent. A contemporary of 'Watchmen' that I vaguely remember reading about was something called, I think, 'Cerebus'. The problem with 'Cerebus' -- and indeed for me, with most modern graphic novels -- was that they were episodic in nature, and if you didn’t buy Issue #1 -- and all those that followed -- then you couldn’t get the whole story, and I was loathe to start reading a single story that I might not finish, might not be able to finish, or that indeed, might never be finished. And now that I think of it, I guess my whole problem with the genre goes way back to my childhood. Many folks my age, who hit their teens in the 1970's, to give a range without being overly specific, grew up reading comic books. They collected comic books and early in their lives got in the habit of buying Issue #1, then Issue #2, and so on, used to the episodic format and the buying habits required to maintain it.

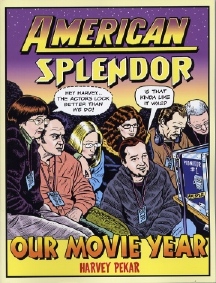

Many years passed, and I fell into the evil ways of the Book Addict, always seeking a new source of Read. And for me, graphic novels were no more Read than marijuana is heroin. I couldn't get a buzz off those words, panels and pictures, no way. Even from the finest graphic novel, like 'Watchmen', though some small, un-addicted part of my brain was able to recognize an interesting substance. The receptor sites were all blocked by something to my mind stronger. The first tiny pinprick in the wall was 'The Book of Ballads'. I didn’t know it then, I thought the dam was plugged, even as I told myself I wanted to open up for the flood. And yes, the real ringer, the kicker, The Opener of the Gate -- to get all Lovecraftian on you -- was Harvey Pekar's 'American Splendor: Our Movie Year'. When I got that, there was no longer a pinprick -- there was a brick loose from the wall. The water was pouring through. I not only read portions of Pekar's latest opus, I went back to the 'The Book of Ballads'.

The reading experiences offered by a typeset novel -- even if it's illustrated -- and a graphic novel -- even if it's laden with words -- are quite different. When you are immersed in a typeset novel, you as a reader are creating a sort of movie experience in your mind. Some writers create a more cinematic experience and others a more abstract experience. As you read, the words flow from the page at a rate you the reader have some control over, though often not as much as you’d like. Some books can't be read fast enough, while others a reader will slow down to savor, page by page, paragraph by paragraph, sentence by sentence, word by word. The reading experience is words-only, and the reader's ability to convert those words into the reading experience is the key to enjoying the work.

In the first place, many of the so-called graphic novels are not graphic novels in the sense that 'Watchmen' was. They're episodic montage narratives, or disconnected short story collections. Not that I'm holding that against them, though I prefer reading novels to short fiction, and that certainly plays into my disinclination to read graphic novels. Moreover, even if they are novels, they're often released in serial form. The Issue #1 rule takes effect and puts the bar up against me reading them, so I don't -- until they come out in an omnibus format, as did 'Watchmen'. But damn it, it's the words and pictures that threw me at first, even when I wanted, I really wanted to read them. You see, as I pick up a graphic novel to read, I'd just speed through the words and glance at the pictures, applying the same reading sensibility to the graphic novel that I did to the typeset novel. That style of reading renders the graphic novel into an annoyingly vapid and underwhelming reading experience. The pictures then lack the fullness of illustrations and the words lack the richness of a novel. The experience won’t gel correctly if you read graphic novels like novels. So it was helpful to have the Pekar, the Vess and the Gaiman books available. For me, the three of them provided an entrée into the world of reading graphic novels, helped me build -- and I can't believe I'm saying this, but it makes perfect sense -- the graphic novel reading abilities I lacked.

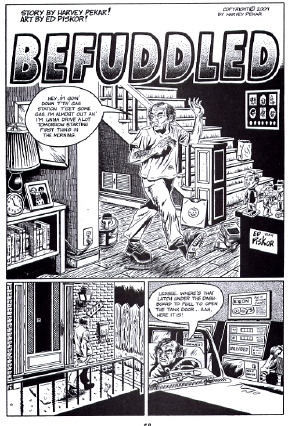

Pekar sucked me in from the start with his winning, "just-me, folks" voice. The first piece in the book, 'Our Movie Year', illustrated by Gary Dumm was simply very engaging. Dumm's art was a rather transparent addition to the prose, for me, and I was able to assimilate the story without changing my reading habits substantially. But this story was pretty atypical, both as a Harvey Pekar tale and as a graphic story. It was highly text driven, and the text was about Harvey's adventures in Hollowood, not about his quotidian life as a file clerk. But a bit further in, I encountered a story that was more typical of the graphic format and Pekar's work, 'Waiting for a Jump', with art by Gerry Shamray that veered wildly from photo-realistic montage work to line drawings. Confronted with a full-page drawing that had only six words, I realized I shouldn't be zipping past it at light speed, even though I already had. So I went back and re-read the story, but I re-read it as a graphic story. When I came to the page with six words on it I spent some time taking in the picture, then read the words.

So, with the Pekar experience under my reading belt, I took my time, working to enjoy and assimilate the details in Vess' illustrations. As I did so, I realized that these details are part of the story telling process, an essential part. One needs to pay attention to the changes; for example there are a series of spine-like projections that slowly seems to emerge from the back of the False Knight as the panels progress. They're never mentioned in the Gaiman's words, and one of the interesting factors for me in reading this --and the other stories -- was my curiosity as to precisely how scripted the stories were. Did Gaiman hand over the sort of "stick figures" that Pekar at one point mentions? Whatever the case, the fact that they weren't alluded to in the narrative portion of the story proved to me to be a plus, adding a layer of visual ambiguity and complexity that the words simply were not capable of conveying. I thought, as I finished reading the story that I was beginning to get it.

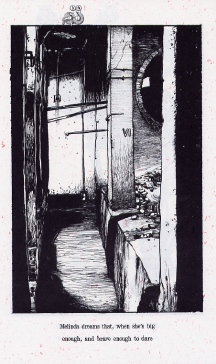

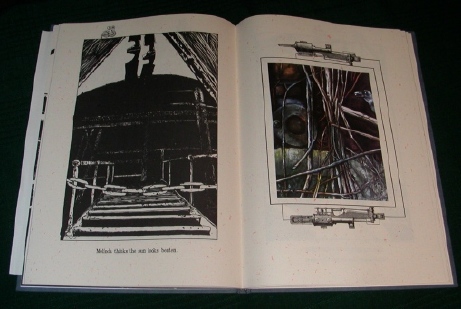

In Vess' collection, it's the art that provides the analog of the story arc, the thread of connectivity between the tales, even though this is not a novel, but clearly a collection of short stories. In the Pekar collection, it's his voice that provides the thread of connectivity, the narrative arc that holds the collection together. But neither of these is a single work, per se. For that, I went to Neil Gaiman -- again -- and the Hill House production 'Melinda'. As usual, Hill House leaves all comers behind. Now this is not to say that I enjoyed the other works more or less, but the production values of the Hill House volume are far beyond those of any other graphic work I've ever seen. As in the Vess story, Gaiman strives for and achieves a tone of muted beauty, telling the story of a young girl wandering about a surreal city. The story is told not in panels, but typeset in short sentences on pages where designer and illustrator Dagmara Matuszak creates an incredibly complex and detailed visual space that neatly teaches the novice graphic novel reader to slow the hell down and absorb the glorious details that are integral to the story.

So I went from book to book, from landscape to landscape. In the process I reviewed 'The Book of Ballads', and 'American Splendor: Our Movie Year'. In fact, I was so inspired by 'American Splendor: Our Movie Year', I even out together a Harvey Pekar-style graphic review of the book. Damn, it was too much fun.

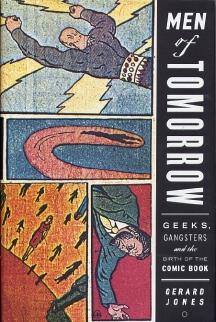

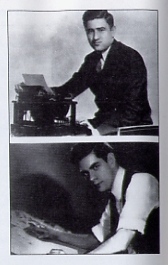

Gerard focuses his stories on two pairs of men. Harry Donnenfeld and Jack Liebowitz were the publishers, while Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were the geeky kids. But he cuts his story as if it were a movie, beginning with Jerry's understandably unhappy response when he heard the details unfold as the first Superman movie was being made. Siegel was incensed, publishing a letter deriding the "INFERNAL, SICKENING SUPER-STENCH," that "EMANATES FROM THE NATIONAL PERIODICALS." Then from there, we're back to the beginning, when Siegel and Shuster were just kids who wanted to create another world. That world turns out to be our world -- a world where comics have become not just an entertainment, but an art form.

Now, as to the contest I alluded to elsewhere...send me an email. Put in the subject GN Contest. Include your mailing address in the message itself. You have until say -- January 5, 2005 to do so. I'll print out the entries, put 'em in a hat, and draw the names of the lucky winners, who will be mailed some books. I'm on the road right now, so I can't even say what they'll be, or how many they'll be. It depends on what I can wheedle out of the publishers. |